During the 1683 Battle of Vienna,

relief came out of the woods and down from the heights...

by Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

For nearly two long months, from

July 14 to early September 1683, Vienna endured the siege of a vast Turkish

army. The Turkish Serasker (Supreme Commander), Grand Vizier Kara “Black”

Mustafa, demanded surrender, but Count Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg, commander

of Vienna’s garrison, spat back, “Let him come; I’ll fight to the last drop of

blood.”

That last drop of blood had

almost been reached. Turkish mines and bombardment opened huge gaps in the city

walls. Sewage, rubble, and corpses littered the streets and disease ran

rampant. After fending off 18 major Turkish assaults, only a third of the originally

11,500-strong garrison remained fit for combat and their munitions were nearly

exhausted. Starhemberg knew that Vienna’s defenses were at their end. The

city’s only hope was the timely arrival of the anxiously awaited Christian

relief army. Without that army, the Turks would pour into the city and wantonly

enslave and butcher its inhabitants.

That last drop of blood had

almost been reached. Turkish mines and bombardment opened huge gaps in the city

walls. Sewage, rubble, and corpses littered the streets and disease ran

rampant. After fending off 18 major Turkish assaults, only a third of the originally

11,500-strong garrison remained fit for combat and their munitions were nearly

exhausted. Starhemberg knew that Vienna’s defenses were at their end. The

city’s only hope was the timely arrival of the anxiously awaited Christian

relief army. Without that army, the Turks would pour into the city and wantonly

enslave and butcher its inhabitants.

Mustafa’s Fierce Ambition

At least Starhemberg

could take heart in knowing that conditions were little better among the enemy.

Among the Turks disease was out of control owing to inadequate sanitary

facilities, casualties were horrendous, and morale was sagging. Worse still,

there were rumors of an immense Christian army approaching from the Vienna

Woods. Nonetheless, Mustafa’s confidence in victory remained undiminished.

Mustafa had another reason to

press on; he feared the Sultan’s punishment in the event of failure. By laying

siege to Vienna, Mustafa disobeyed Sultan Mehmed IV (1648-1687), who intended

that Mustafa do little more than capture Imperial frontier fortresses. But such

modest aims did not satisfy Mustafa.

Outwardly handsome, dignified,

and a devout Muslim, inwardly the Grand Vizier was an arrogant power monger

with an unveiled hatred of Christians. His one redeeming quality was his

personal bravery, but even this was tarnished by acts of extreme brutality; he

once flayed captured Poles alive and sent their stuffed hides to the Sultan as

trophies. Mustafa cared only for his own career and freely used deceit and

blackmail to make up for his lack of any real talent. Determined to follow in

the footsteps of the great Islamic conquerors of old, Mustafa had set out to

overcome the barrier that once before, in 1529, blocked the westward advance of

the Ottoman Turks: Vienna, capital of the Holy Roman Empire and of the Imperial

dynasty, the House of Hapsburg.

Leopold I Pleads for Help

In contrast to the offensive

spirit of Mustafa, Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I (1658-1705) cowardly fled his

own capital for the safety of Passau. A bookworm and music composer, the pious

Leopold wasn’t much of a warrior. But he wasn’t going to abandon his capital to

the Turks either and feverishly petitioned the German and Polish nobility to

come to Vienna’s aid.

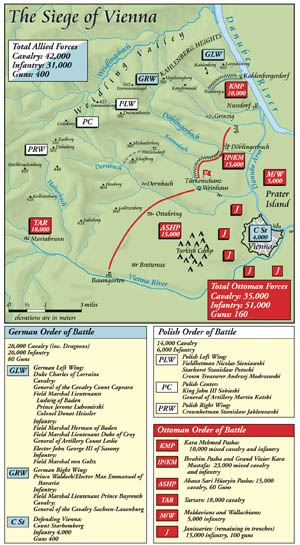

Leopold’s cries for help did not

remain unanswered. By September 7 a mighty army had gathered in the Tulln

valley. There was John III Sobieski, King of Poland and Duke of Lithuania, with

18,000 Poles; the Elector Max Emmanuel of Bavaria with 11,000 men; and Prince

George Friedrich von Waldeck with 8,000 Germans from Franconia and Swabia.

Prince George of Hanover (the future King George I of England) arrived with a

bodyguard of 600 cavalry sent by his father Duke Ernst August of Hanover, and

there were 9,000 Saxons led by the Elector of Saxony, John George III von

Wettin. Together with Imperial General Lieutenant Duke Charles of Lorraine’s

20,000 Austrians, the allied army numbered over 66,600.

Many princely volunteers

accompanied them, including young Prince Eugene of Savoy. Recently defected

from the service of Louis XIV, Eugene brought nothing but his sword and steed.

The “Prince volontaire” would be fighting with the Austro-German cavalry.

With so many prominent nobles,

quarrels over command were unavoidable but were resolved through the

selflessness of the Duke of Lorraine. Although cursed with a pockmarked face

and a limp leg, his proven combat history against both the Turks and the

French, his personal courage, humility, and charm gained everyone’s affection

and admiration. On Lorraine’s recommendation, Supreme Command was given to

Sobieski, King of Poland. Sobieski, who refused to serve under anyone, held the

highest rank and had demonstrated his valor and skill by defeating the Turks at

Khocizm in 1673. Albeit past his prime and so fat as to be unable to mount his

horse without assistance, Sobieski nevertheless retained a sharp mind and,

decked out in luxurious garb and armor, still looked the part of a charismatic

commander-in-chief. Lorraine’s Plan to Squeeze the TurksSobieski would lead the Poles

while Lorraine nominally commanded the Austro-German forces. Beyond this each

commander led his own men while adhering to Lorraine’s tactical plan. The idea

was to march the army from Tulln through the Vienna Woods to the Kahlenberg

heights (“berg” in German means height or mountain). From the heights a broad,

sweeping descent would squeeze the Turks against the city, the Danube arm, and

the Vienna River. The approach denied the Turks the natural defenses of the

aforementioned rivers and, because the allies would emerge from out of the

wilderness, they hoped to catch their enemy unprepared.By the 10th the main army reached

the Weidling Valley on the northwestern side of the Kahlenberg. Colonel Donat

Heissler’s vanguard of 600 dragoons had already reached the Kahlenberg heights

three days prior, to light fires and alert Vienna of its impending relief.

Early in the morning of the 11th, Lorraine sent reinforcements to Heissler, who

led his dragoons, musketeers, and a band of Italian volunteers against the

Turkish outposts at the Chapel of St. Leopold and the ruined Camuldensian

monastery. After routing the Turks from the Christian holy places, Heissler

launched signal flares into the night sky. To the defenders on Vienna’s battered

walls, Heissler’s fires and flares were like a sign from God that their prayers

had finally been answered.At 11 in the morning of the 11th,

the Austro-German contingent moved into position on the heights, between

Leopoldsberg and the Hermannskogel: Lorraine and John George with Imperials and

Saxons on the left and Waldeck and Max Emmanuel with Franconians, Bavarians,

and Imperials on their right. Both contingents placed their cavalry on their

outer flanks. The Poles, meanwhile, were still struggling to cross the

Weidlingsbach to form the honorable right wing of the allied army, between

Rosskopf and Dreimarkstein.

Later that day, the princes and

generals met on the ridge to behold a panorama of the siege. Below them Turkish

siege works and camps surrounded the city, wedged beneath the Vienna River to

the south and the Danube arm to the north. A dim haze of smoke rose from the

constant artillery barrage, exploding mines, and campfires. More worrisome was

the rugged terrain of precipices, ravines, and woodlands that led down from the

hills to the plain below.

Angered, Sobieski claimed that

the maps sent to him by Imperial commanders had misled him. He expected the

terrain to have been far more level and now proposed either a detour to the

south or a slow, meticulous advance. These ideas were stoutly overruled by the

other generals who decided to continue with Lorraine’s original idea of a

full-scale attack from the ridges of the Vienna Woods. Although the terrain was

rough it was noted that Mustafa had done very little to fortify his besieging

army. Nevertheless, the Polish king did manage to gain the transfer of four

Hapsburg infantry battalions to support the Polish cavalry.That night Lorraine ordered his

general of artillery, Count James Leslie, to place a battery along the edges of

the Kahlenberg to provide supportive fire for the main advance. While the

artillerymen labored, cries of “Allah” and the incessant artillery bombardment

of Vienna robbed many of the Christians of their deserved sleep. Moreover, the

previous day’s march had been carried out at great speed in the face of

difficult terrain and stormy weather. To lighten the load, many supplies were

left behind, leaving the men with empty stomachs and forcing the horses to feed

on leaves. Despite these hardships morale remained high.

The Ottomans Await the Christian

AttackBelow the Christians,

over 70,000 Ottomans and auxiliaries, deployed between the Danube and the

Vienna Rivers, awaited the Christian attack, surprise having been passed. Kara

Mehmed Pasha, Beylerbeyi of Diyarbakir, with 10,000 troops—including the

Bosnian-Rumelians, centered on the Nussberg—made up the right wing. Behind him,

on Prater Island, there were a further 5,000 Moldavian and Wallachian

reinforcements.

The bulk of the Turkish center

under Ibrahim Pasha, Beylerbeyi of Buda, and Kara Mustafa occupied the

fortified ridges above the Döblingerbach and Krottenbach up to Weinhaus.

Ibrahim and Mustafa’s forces, made up of cavalry, seymen peasant militia, and janissary

infantry, were about 23,000 strong. Beside them, on their left, Abaza Sari

Hüseyin Pasha, Beylerbeyi of Damascus, commanded the rest of the central line.

His 15,000, mostly cavalry, units covered the Weinhaus-Ottakring-Baumgarten

line with smaller detachments deployed in the Schafberg area to slow down and

hamper the initial Christian advance. Here the walls and buildings of numerous

vineyards provided shelter for the defenders.

Along the northern bank of the

Vienna River, on the left wing near Mariabrunn, stood 18,000 Tartars. “By

Allah, the King is really among us,” blurted their Kahn when he discovered that

Sobieski himself led the relief army. In a decision opposed by Ibrahim Pasha

but approved by the other senior generals, Kara Mustafa decreed that the

remaining 15,000 janissaries and provincial troops would continue the siege of

Vienna.

The Battle BeginsAt 5 am on the 12th, Kara

Mehmed’s vanguard opened the battle by attempting to disrupt the deployment of

Leslie’s artillery. From his viewpoint at the ruined monastery, Lorraine

noticed that an advance of the whole Turkish right accompanied the attack on

the battery. In response, Lorraine sent reinforcements to Leslie and ordered

the advance of the Austro-German left wing. By sunrise, of what came to be a

sunny and clear day, Waldeck and Max Emmanuel also received orders to begin the

descent. After informing Sobieski of his actions and gaining his approval,

Lorraine hurried off to lead the Austro-Saxon troops pouring down the defiles

of the Kahlenberg. The Polish king prepared himself for battle by attending a

Mass held in the Chapel of St. Leopold.To the Turks it seemed “as if an

all consuming flood of black pitch was flowing down the hills” at whose head

fluttered proudly a large red flag with a white cross. Lorraine’s main concern

was the maintenance of a unified front, a daunting task due to the uneven

ground.

Reinforced by Duke Eugene of

Croy’s infantry, the Austrians routed the Turks firing at Leslie’s artillery

and together with John George’s Saxons to their right established a line facing

the Nussberg-Karpfenwald. Supported by light artillery fire and maintaining an

unrelenting barrage of musketry fire, the Austrians slowly but steadily

advanced up the Nussberg. Here there was stiffening resistance by the Turks,

who skillfully used the cover of the terrain to their advantage. An Imperial

regiment that had reached the outskirts of Nussdorf was repulsed, while the

Turks still holding Kahlenbergerdorf threatened the Austrian left flank.

Lorraine ordered Count Caprara to

storm Kahlenbergerdorf from the shoulder of the Leopoldsberg. With Heissler in

the lead, the dragoons encountered initially heavy resistance but, supported by

Prince Jerome Lubomirski’s heavy cavalry, seized Kahlenbergerdorf and advanced

beyond it. But Mehmed’s men, now reinforced by seymen, rallied and threw the

Christians back to the village. On its outskirts, the Turks fell upon the

wounded, beheading the dead and dying.

By 10 am the German left wing

occupied the rim of the Nussberg. Unfortunately, on their right Waldeck and Max

Emmanuel had failed to keep up with Lorraine’s advance. This exposed the right

flank of the Saxons, who had veered left from the Karpfenwald to bolster the

Austrian attack on the Turkish Nussberg positions. Lorraine called for a halt

to allow Waldeck and the second and third Austro-Saxon battle lines to catch up

and reestablish a solid front. Joined by John George, Lorraine hurried off to

the front line to take personal charge of the German soldiers. Sobieski,

meanwhile, left the Chapel to hasten the movement of the Poles who still had

not arrived in position south of Waldeck.Recognizing the loss of the

Nussberg to be a serious threat to their right flank, the Grand Vizier and

Ibrahim Pasha mounted a vicious counterattack but were pushed back into the

flatter terrain around Grinzig. A second assault proved more successful so that

the Imperial infantry began to waver but was saved by the arrival of dragoons

and the elite armored cuirassier heavy cavalry. John George and his bodyguard

cavalry took part in the action. Wounded in the cheek by an arrow, the Saxon

Elector cut down a Syrian lancer. Pursuing their advantage, the Saxons advanced

down the Muckental in the direction of Heiligenstadt while the Austrians moved

toward Nussdorf.

The Attack on Nussdorf

Supported by Leslie’s artillery,

now deployed on the Nussberg, and Caprara’s advance from Kahlenbergerdorf,

Saxon and Imperial dragoons under Margrave Ludwig Wilhelm of Baden and Heissler

led the attack on Nussdorf. Entrenched in the village cellars, ditches, and

ruined walls, the Turks put up fierce resistance and were only overcome by the

arrival of Wilhelm’s uncle, Field Marshal Herman of Baden, leading the Austrian

infantry. To the south, Field Marshal von Goltz’s Saxons successfully drove the

Turks from Heiligenstadt and Grinzig.

At noon Lorraine called for

another halt to allow his troops to recuperate. The morning’s actions had been

a complete success. The whole Turkish right wing of Kara Mehmed was completely

overrun or destroyed. The Austro-Saxons now faced Ibrahim Pasha across the

Döblingerbach. Waldeck and Max Emmanuel, who had encountered little opposition,

reached Ibrahim’s flank across the Krottenbach while Caprara and Lubomirski

scattered the Romanians along the Danube.

The Poles Enter the Fray

The Poles finally appeared on the

heights after an exhausting march through the rough terrain of the Weidling

Valley. In the center, Sobieski with Artillery General Martin Katski descended

from the Gränberg. On the left, Fieldhetman Nicolas Sieniawski came down from

the Dreimarkstein, and on the right Crownhetman Stanislaw Jablonowski came down

from the Rosskopf. Polish infantry and the borrowed Hapsburg battalions

screened the descent to allow the establishment of an unbroken cavalry front on

the plains below.

Thorn bushes, grapevines,

ditches, hedge-rows and individual gönüllü suicide charges slowed

down the Polish advance. Nevertheless, in spite of a spirited defense by Abaza

Sari Hüseyin, the Poles, supported by artillery fire, steadily pushed forward.

With Sobieski in the lead the Michaelerberg was reached by 2 pm. The Germans,

who now came into view, gave off a terrific cheer upon spotting the arrival of

their Polish allies.

Beyond the Michaelerberg, on the

slopes of the Schafberg, the Poles were brought to a momentary halt. Ahead of

Sieniawski, 1,000 janissaries infiltrated the vineyards behind Plötzleinsdorf,

disrupting the junction between Sieniawski and Waldeck’s right wing. The

janissaries put up a stout defense but were dislodged with the arrival of

Imperial cuirassiers.

Around 4 in the

afternoon, Sobieski and Sieniawski reached the level terrain east of the

Schafberg. On their right Jablonowski fended off a feeble attack by the Tartars

near Mariabrunn. Sobieski now called a halt in order to build a more organized

and solid front. Kara Mustafa, aware of the new Polish threat to the Turkish

left wing, used the respite to withdraw troops from Ibrahim in order to bolster

Hüseyin Pasha.

The Poles Cavalry Units Get

Butchered

Sieniawski reopened the battle by

sending out achoragiew (standard Polish cavalry unit) of Crown hussars.

These crashed through two enemy lines but the 150 or so horsemen were unequal

to the task. Forced to retreat they lost a third of their number.

Falsely anticipating an Ottoman

advance the overzealous Sieniawski sent in a second choragiew. Stanislaw

Potocki, Starhorst of Halicz, volunteered to lead the charge. Again the Poles

broke through the Turkish ranks and again the Turks rallied to close the gap.

Stanislaw paid for his bravery with his life; a Turk sliced off the top of the

Pole’s head.

Further units of Polish cavalry

now charged the Turks who opened their ranks and then fell upon the Poles from

all sides, inflicting heavy casualties and killing several Polish lords, including

Andrzej Modrzewski, the Crown Grand Treasurer. The slaughter was followed by an

all-out Turkish pursuit, which soon came under fire from the Hapsburg infantry

on the Galitzenberg. Reinforcements from Sobieski’s center and the timely

arrival of dragoons and cuirassiers from the German right helped stop the Turks

in their tracks.

With the withering of the Turkish

assault and Jablonowski occupying the Galitzenberg on the Polish right,

Sobieski at last established an unbroken line for the next advance. North of

the Poles the Germans had long since recuperated. Despite the heat and the

exertions of the morning’s battle, the troopers were so eager to advance that

officers were forced to restrain them with the flat of the blade. Facing them

was Ibrahim Pasha on the ridges above the Krottenbach-Döblingerbach. The

Turkish position was the strongest along the entire front but had been weakened

by the dispatches sent to face the Poles.

Lorraine Hesitates: Stop for the

Day or Continue the Attack?

At this critical moment in the

battle Lorraine hesitated. Conferring with the Saxon commanders, the duke could

not decide whether another war council should be held to decide if the day’s

progress was sufficient or whether to continue attacking. To this the venerable

von Goltz replied that “God is pointing the way to victory … strike while the

iron is still hot.” Pleased with Goltz’s advice, Lorraine shouted “Allons

marchons!”

The attack opened with a terrific

barrage of musketry fire from the Christian squares, demoralizing and thinning

the Turkish defense. At around 5 pm the Franconians and Bavarians launched an

assault on the Türkenschanz, the location of the Holy Banner. Ibrahim Pasha’s

entire front now collapsed, opening the way to Vienna. Instead of moving toward

the city, however, Lorraine recognized the opportunity to strike at the right

flank of Hüseyin Pasha, who was currently getting ready to withstand Sobieski’s

all-out advance. Like Lorraine, Sobieski had at first been content with the

day’s gains but was persuaded to continue the battle by the aggressive spirit

of Sieniawski and the Germans.

With the cry of “Jezus Maria

ratuj” (Jesus Maria help.”) the whole Polish line rode down upon the Turks.

Encased in glittering steel that covered head to thighs, with their tiger and

leopard pelts fluttering in the wind and eagles’ wings affixed to their backs,

the leading units of hussars presented an almost unearthly spectacle. Armed to

the teeth with a 19-foot pennon-tipped kopia lance, a curved and a

straight saber, four pistols, and a battle hammer, and mounted on a powerful

armored steed, the hussar was the epitome of the Polish cavalier.

Following the hussars

were pancerny and kwarciany. Likewise made up of Polish

aristocrats, the cavalrymen of the pancerny wore helmets, mailed

shirts and shields and wielded short lances, falchions, the handzar dagger,

poleaxes, and musketoons or bows. The kwarciany light cavalry of the

poor Polish gentry and foreigners wore little armor and brandished short

lances, sabers, and the occasional pistol. Leading the whole attack was

Sobieski himself, his armor decked out in blue, luxurious semi-Oriental garb,

his hand holding thebulawa marshal’s baton. On his side, curved saber in

hand, rode 14-year-old Prince Jakób.

Slowed by vineyards and uneven

terrain, the heavy Polish cavalry did not pick up speed until it reached the

open terrain of the Baumgarten-Ottakring-Weinhaus area, where it ran into

Turkish skirmishers and artillery fire. Turkish guns ripped through the Polish

ranks but the charge of the cavaliers proved unstoppable. Like thunder, the

shattering of Polish lances resounded over the battlefield as the cavalry

overwhelmed the Turkish battle line. Sobieski followed on the heel of his

hussars, capturing the Turkish guns while the Turks, demoralized by Lorraine’s

advance on their right flank, rallied toward their left wing opposite

Jablonowski.

Mustafa Attempts to Rally the

TurksIn the Ottoman center, Kara

Mustafa entered the fray personally to prevent the imminent capture of the Holy

Banner by Waldeck’s steadily advancing Franconian-Bavarian foot. Flanked by sipâhî andsilâhdar (two

forms of cavalry; see sidebar), the Grand Vizier charged against a rain of

German cannon and musket fire. Mustafa grasped the banner but all around him

the Turkish attack crumbled, his men fleeing toward the Vienna River.

Simultaneously the Ottoman left wing completely disintegrated as Sobieski led

the combined forces against the Turks who had rallied in the Breitensee area.Boiling with vengeance, Mustafa

ordered the troops in the trenches to stop the bombardment of the city and

called for the destruction of equipment and massacre of captives. Mustafa knew

the battle was lost but his will to fight remained undiminished. With lance in

hand he led his personal bodyguard in a heroic but doomed assault against the

Christians. One by one his personal retainers, his private secretary, numerous

pages, and his whole Albanian bodyguard fell to the fire and swords of the

infidel. Only the argument that his own death would cause the destruction of

the remaining Ottoman troops persuaded Mustafa to break off the melee. Seizing

the Holy Banner of the Prophet and his private treasure, the Grand Vizier fled

the battlefield at around 6 in the evening to lead the retreat back to Györ.

Erroneously fearing that the Turks might rally and counterattack, Sobieski

forbade a full-scale pursuit and ordered his men to stay on guard.

Vienna is RelievedLorraine’s forces, meanwhile,

established contact with Starhemberg, who sallied out of the Schottentor to

join the battle. Ludwig Wilhelm of Baden and his dragoons were given the honor

of relieving the city. After marching up to the gate to the joyful tune of

kettledrums and trumpets, the dragoons joined the defenders in cleaning out the

few remaining Turks. At around 10 pm, after a further 600 Muslims were cut

down, the battle came to an end. In the Turkish camp, Christian infants and

children cringed among hundreds of butchered captives. Starhemberg’s garrison

took revenge by burning the 3,000 abandoned Ottoman sick and wounded alive. In

all the Turks suffered 15,000 casualties compared to 1,500 for the allies.

Sobieski ordered the German

forces around the Türkenschanz and Jablonowski’s wing on the banks of the

Vienna River to remain at guard throughout the night. A few Polish squadrons

hunted down Ottoman stragglers beyond the Vienna River. However, Sobieski’s and

Sieniawski’s own contingents, located as they were at the Muslim main camp,

could not control themselves. Order and discipline broke down as the Poles

feverishly pillaged the pick of the Muslim spoils. Instead of chastising his

troops, Sobieski acquired the lion’s share of the loot for himself. Within the

Grand Vizier’s pavilion, with its lavish courtyards, dining halls, baths, and

gardens, the King found heaps of golden and bejeweled treasures.On the 13th Sobieski conducted a

Roman-style triumphal march into Vienna to the cheers of the populace, who

cried, “Long live the king of Poland.” Sobieski’s egotism came as a bad affront

to the Austro-Germans. The premature looting of the Poles was bad enough, but

Sobieski’s entry into Vienna before the Emperor was an insulting breach of

protocol. Lorraine particularly was disgusted by Sobieski’s vanity, which on

the 13th prevented an opportune pursuit of the demoralized enemy and allowed

Mustafa to carry thousands of Christian children into captivity.

Leopold Returns to Vienna On the morning of the

14th the Germans rummaged through whatever loot remained at the Turkish camp.

Around noon the electors Max Emmanuel of Bavaria and John George III of Saxony

met Emperor Leopold himself at Vienna’s gates. Surveying his devastated

capital, Leopold found many of the buildings in ruins, although thankfully the

limited range of the Turkish artillery had left much of the interior of the

city untouched. Upon hearing the news of Sobieski’s march into the city,

Leopold became greatly aggravated. He so lost his nerve that he tactlessly paid

little attention to Lorraine’s problems of provisioning the relief force or

those of George III who, being a strong Protestant, brought up the matter of

Leopold’s mistreatment of the Hungarians. Fed up, John George III marched his

troops back to Saxony.

The next day Leopold rode out to

the Polish camp at Schwechat to visit the self-proclaimed savior of Vienna. The

meeting began well but deteriorated when Leopold coldly ignored the presence of

Sobieski’s son Jakób, whom Sobieski had hoped to marry to Leopold’s daughter.

Jakób showed his good nature by taking no offense, but his father, urged on by

his anti-Hapsburg Francophile nobles, magnified the incident to such a degree

that his relationship with Leopold remained forever strained.

Nevertheless, Sobieski remained

to lead the pursuit of the Turks. At Parkan on the 28th, he and Lorraine

annihilated a Turkish corps. With the remaining Turks on the retreat back to

Belgrade, the towns that had submitted to the Sultan now reaffirmed their

allegiance to the Emperor.

While the allied victory had

strained, rather than cemented, the ties between the Holy Roman Empire and

Poland, the rest of Christendom celebrated. In the streets of Vienna and in the

cities of Austria and all through Europe there was a feeling of euphoria. It

was the greatest victory over the Turks since Don John of Austria’s 1571

victory at Lepanto over the Sultan’s armada. For his heroic defense of the

city, Starhemberg was awarded 100,000 crowns, the Order of the Golden Fleece,

and the title of field marshal.

A Huge Loss for the Ottomans

The magnitude of the defeat was

not lost to Kara Mustafa who sought to escape the Sultan’s vengeance by blaming

his defeat on subordinate commanders, executing those that might inform the

Sultan of the Grand Vizier’s mishandling of the Ottoman army.

Mehmed IV remained unconvinced.

During the battle, the Christian commanders and troopers fought with skill and

courage while, tactically, their attack through the Vienna Woods wisely avoided

the natural defenses of the Danube and Vienna Rivers. Nevertheless, their

victory was not so much due to any Christian brilliance as it was to Mustafa’s

negligence and arrogance. By failing to properly fortify his army from an

outside attack and leaving many of his janissary units in the trenches

surrounding Vienna, the Grand Vizier sealed the fate of his army.

Mustafa would pay for his

failure. On December 25, 1683, while staying in the palace at Belgrade, the

sultan’s emissaries executed the Grand Vizier by strangulation and sent his

head to Constantinople.

The sultan’s anger was not

unfounded. A Turkish victory would not have meant the end of free Christendom,

because France would have presented a bulwark to further Ottoman expansion.

However, Austria was saved and, more importantly, the initiative passed to the

Holy Roman Empire. After hundreds of years of warfare the Christians had turned

the tide against the sword of Islam. Under Max Emmanuel, Ludwig Wilhelm “Türken

Louis” of Baden and above all Lorraine and Prince Eugene of Savoy, the Holy

Roman Empire would slowly but surely roll back the Ottoman hold on Eastern

Europe.